UPDATE (3/29/20): I was going to be living, studying, interning, learning, and experiencing in Senegal from January to May of this year — an incredible opportunity that I wanted to squeeze every ounce from. However, the COVID-19 pandemic dictated otherwise.

To my dismay, I returned home on 3/18 due to the worsening global crisis. The processing + learning from those two months there, though, are nowhere near finished. I miss the people, places, and times greatly.

Please enjoy the blog posts, pictures, and other updates of note below. They form a by and large detailed record of my time in Senegal. As before, there are two introductory pieces at the very beginning that seemed like a good place to start — one reflecting on travel, and one reflecting on where I come from, and where I went.

Making Bouye as the World Burns; or, Ba Beneen Yoon Sénégal

Note: This was written my first through fourth weeks — not in Senegal — but home in Milwaukee, and posted on 4/15. It was easily the most difficult to do.

A hair over five weeks have come and gone since my last glass.

It was a tall one, a cool one, thankfully not too sweet and infused with a slight tang. Maman brought it over that afternoon, with a distinct rap on my door; “Jacques! Une verre de bouye pour toi!” she would say in her ever-efficient way, already shuffled along determinedly to her next matriarchal task before the liquid can touch my lips.

The production of this juice — bouye — one of Senegal’s beloved local varieties, is an arduous activity. Not that I would know first-hand, of course; a foreign toubab like me wouldn’t be entrusted to the process in a million years. But I promise you, it certainly seems to be. Or if nothing else, sounds that way.

As you’ve read by now, I am — err… I was — peppered day-in-and-out by a litany of household noises diverse enough to drop an album: *Bright lights* Just released! *Flashbulbs* Studio Sessions: Jake’s Mermoz Bedroom. This truly isn’t a stretch of the imagination. We’d lead off, I think, with the cat’s yowl; followed by a jolting outburst of Wolof between fake-annoyed family members (arguing loudly with great frequency is a sign of love here). This would be overdubbed with that damn rooster’s 6am caw; oh, and throw on a feature collab by a hot new duo — my Cousin and the Sacrificial Sheep.

Plus, each Thursday morning, shaken from slumber by the uniquely satisfying thwack of a pestle on mortar, we could mix in another track.

On that specific one, 35 days that feel like months ago, I awoke to an unpleasant feeling. It wasn’t just, in fact, due to the pinging alerts on my phone I stumbled over to crusty-eyed — panicked messages from multiple friends in Europe, hearing word they’d be immediately sent home from their study abroad programs due to COVID-19. I mean, are you kidding me?!

No, at 08:30 my primary concern happened to be diarrhea.

Weathering (and withering) the third day of a nasty stomach bug, there was already a sinewy knot in my gut when I found out the situation a mere hop, skip, and jump from Senegal. Rather than my friends, though, it should regretfully be noted that the first call of the day had to be the bathroom.

The family bouye, however, is made directly between my door and la toilette, and like I said, is quite an operation. It’s money-making, too; dozens of 1.5L plastic bottles will be filled to sell by day’s end. Bouye is a product of the baobab tree — but more specifically its fruit — which is known as pain de singe (monkey bread) due to a certain animal’s affinity for the loaf-shaped, hanging gourds. In our house, the distillation of the stringy, white inner pulp to something remotely consumable is directed by one juice-master — a wizened and wrinkled little Senegalese lady brought in for that express purpose.

But as wholesome as that may be, I’ve got the runs, and she’s in the way. After awkwardly edging with back to the wall around her chair, some large tubs of water, and a clay mortar filled with ground fruit, I reach my destination, albeit seriously queasy. I swear she gives a knowing side-eye when I slink sheepishly back to my room, relieved to feel slightly less shitty (literally…).

Unfortunately, the good-ish feeling wouldn’t last. By the time Maman brought ‘round the bouye for my angry insides (“So good, so good for digestion,” she says at least three times in her endearingly halting French), my friends will have already scramble-booked flights home, travel will be suspended to 14 different European countries, and a palpable unease will have settled over us MSID’ers in Dakar. Senegal had recorded a handful of cases by this point, but to put it bluntly — as I’d soon be paraphrasing to concerned friends and family — that unforgettable day marked the start of shit (ya know, the metaphorical kind) truly getting real.

So maybe you can see where this is going.

If it’s not yet plainly clear, I’m not writing this from Senegal. I’m not tap-tapping this out on a sun-drenched afternoon from the lively, fronded paradise of the West African Research Center; nor am I tickling the black-and-white keys by the midnight oil, cross-legged in my spartan, yet oddly cozy, host family bedroom. No, to my dismay I can no longer dump backpack on bed, cinch up ever-more frayed laces, and jog over to the friendly gym by the sea. There is, quite simply, no more dust to pound on, no more setting sun to bask in.

As the world reels, and COVID-19 rages, I’ve come home.

It’s no stretch to call it perhaps the most difficult departure of my life. And I’ve had many, as we all do, large and small, notable and entirely unremarkable. For me, the big ones seem to mark time in crisp intervals: going to Beijing and back at 17, leaving for college at 18, beginning full-time apartment living at 19, taking this Atlantic leap at 20… with a hundred more minor ones in between. Heck, without fail I suffer a brief period of mourning after every outdoor trip of mine — cycles of departures, initiations, journeys, wrap-ups, returns, dispersals, reintegrations… all made only marginally easier with the passage of time.

It makes me think of something I wrote a while ago, several years past, long before I could possibly imagine a joyous Muslim baptism, hear myself bartering through countless taxis and markets and fruit stands, or picture a bedroom in some faraway house with strangers turned family. My cap and gown hung patiently in a different bedroom, then, high school just days from the rearview. But really, I wrote, is life not simply an endless cycle of beginnings and ends, take-offs and returns, some as significant as closing the chapter of childhood, others as simple as closing the chapter of a book?

Four years later — childhood wrapped, life narrative far advanced — and this hits home closer than ever; maybe because this time, the chapter doesn’t feel finished. Closure simply isn’t there.

See, our version of scramble-panic arrived on the very first night of spring break, a long-awaited trip into wider Senegal the product of many iterations and hurdles (long story short: Cape Verde Airlines? Just don’t fly them). With 8 of us nestled into a semi-remote AirBnb near a beach town south of Dakar, feeling about as far removed from global crises as a person can, this truth bomb of a header landed in our inboxes at local time 21:56: Senegal Program Suspended – Departure Required

Fuck.

If something, anything, one single morsel of other reaction came in that instant, I’d do due diligence in reporting it. But I’m not convinced anything did — just pure blankness, chalk-white and frothy as a good bouye.

“Well guys, we’re goin’ home,” is the first thing I registered one of my friends saying out of the fuzziness — in a bizarre tone. Not quite sad, not really spiteful, not even shocked… just… fuck.

Matter-of-fact was all we could be. In some ways, it’s still all we can be. How else can you deal with the cognitive + physical dissonance of being uprooted sharply from your newly setting roots, then thrust back down somewhere else — with the added bonus of social distance from your fellow plants?

Because boy, if I thought that sacrificial sheep, Chinese-backed roadside-beachside gyms, or trash-caked neighborhoods were inattendu’s, here, take this heaping course on a communal platter and give yourself a gut punch.

For if the world were not how it is, perhaps in some alternate universe, I’d be in Toubacouta now. Yes, the same Toubacouta as the February field trip, handsy wrestlers and handsy mobs of kids in all. I’d be in week #4 of an agro-ecology internship — getting acquainted with the tendances + inattendu’s of a different family, observing the many fils + racines in a changed light, running the gamut of new’s + not’s once more. I’d so hope to eat around the bowl with them; maybe they’d even make juice, too.

And how can that not weigh on my mind?

Because beyond pity parties (attendees: 1) for my own misfortunes, I worry about, and seriously miss, all the people — teachers, host family, friends — living this out over there. It’s true that for all of the United States’ haughtiness, Senegal has so far done a significantly better job at combatting COVID-19’s spread — only 2 deaths at last count.

But nevertheless, daily life — especially for a culture so deeply community / sharing-oriented — has without doubt taken a major turn. A blanket, daily curfew (20:00 – 06:00) has been put into place, and effectively a nationwide lockdown initiated. I can imagine stoic Gendarmerie officers, the “People’s Army” national police, circling the narrow, now quiet, neighborhood streets — rough sand football matches postponed, rusted-out hoops bent sadly over empty courts, the kids and parents and grandparents forced home. I can imagine all too well the vibrant and hectic Dakar that I knew, at least, being stifled.

So, as the world seems to burn all around, I wonder if the bouye can still be made. Knowing my family, led by Maman’s admirable tenacity, I’m positive they’ll try their absolute darnedest — both for normalcy’s and economic practicality’s sakes. Something’s inexplicably funny about the wrinkled old juice lady pounding the mortar a new one in a tiny surgical gown and gloves, fast-talking Wolof with Maman through a mask, maybe because it’s so believable. At least they could rest assured there wouldn’t be an American with diarrhea interrupting the operation.

But in all seriousness, this “to bouye or not to bouye” question is reflective of so much of my time in Senegal; bouye-making in a literal sense, and also a metaphorical, much larger one. In my two months, I came to notice more, and appreciate, the everyday small things, the taken-for-granted things: simple pleasures, swirled around in a sweet-tart, milky glass; and unnoticed things, like the labor, and clear care, to get it there. Much of the population relies on such non-commercial, person-to-person exchanges for a living, or at least to make ends meet, so this shutdown signals a slippery, slippery slope — just as it does for untold millions here. It’s not a flashy lifestyle they lead, but shouldn’t be any less valued. If anything, more so.

I take a measure of peace, though, in knowing that I’m only a WhatsApp message away. The Senegalese I had the fortune to know were on the whole extraordinarily welcoming, generous, and patient (among many other attributes) — meaning the sudden split from these people may still be the hardest aspect to take. I mean, up to this point, my only true cry since that awful 21:56 email came directly after the final parting from my host family — silent tears rolling down my cheeks en route to the airport, the taxi driver without a doubt wholly confused over this emotional toubab.

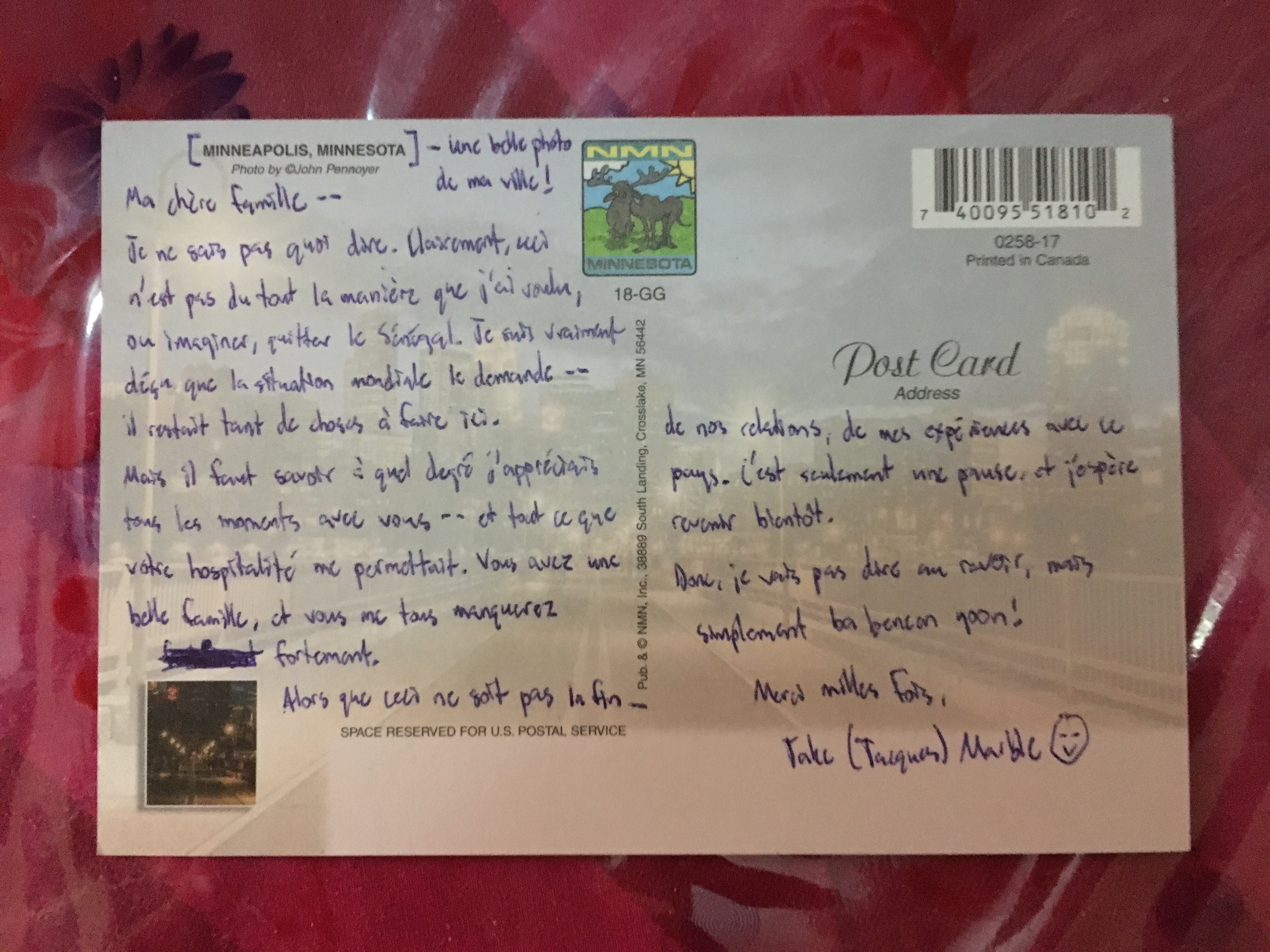

Which is all to say that the rushed good-bye’s choked out to them and my adopted home could not actually be good-bye’s. I couldn’t let them be. Not once — in French, Wolof, or English — did I offer any equivalent to the phrase.

Instead, I kept resorting to one of my newly-learned Wolof favorites: ba beneen yoon. Roughly, until another time. Not a cutting off, just a cutting away. Not a chapter closing, just a page break. Not a good-bye, just a see you later.

I have no idea when I’ll return to Senegal, or if. It will never be for a lack of want. As Maman told me those waning moments, while we lined up for a first and last family picture, I’ll now forever have a home there. Their door is always open. The country’s as well. It’s up to me, and perhaps a little fate, to find a way back in.

And with that, all I can think left to offer is this — a wobbly line scratched to my journal through welling eyes, 35,000 feet due west over another cold, jet-black water. But there’s no déjà vu this time, no flashback to a Mississippi dawn exactly two months prior. There’s only a heavy sort of acceptance in the melange of French and Wolof I pen, epitaph to a chapter interrupted: “Sénégal, tu vas me manquer comme rien d’autre, wánte jeexuloo dans ma vie.”

Senegal, I’ll miss you like nothing else, but you aren’t finished in my life.

Ba beneen yoon, is all.

I can only hope.

Some Final Photos (That Mean a Great Deal)

Masked People, Masked City

Note: This was written throughout my seventh and eighth weeks in Senegal, and posted on 3/12.

I wish I could remember le quartier. Dammit, I should know its name…

As I slump my head heavily against the window of yet another taxi, I can’t shake this thought, and a weird sense of guilt. Briny ocean air ripples over the sooty glass, slicking my hair back. It’s baking hot, of course, but I really shouldn’t have it open at all. See, our first Dakar dust storm arrived today — though dust blanket might be a more accurate term.

The stormy part was yesterday. Unusually high winds buffeted the peninsula in strong waves, and those mixed with unseasonal clouds created mild temperatures. What was brought by the front, however, was not rain (as that, during the dry season, is near impossible), but dust — a desert mixture that’s suspended over the cityscape like burnished fog. It reminds me a bit of the first snowfall back home, a soft papering over everything and everyone that causes minor overreaction en masse.

Due to this maybe, I must admit that my morning kicked off a little arrogantly. Compounded with some five weeks of swallowing sand gusts, eating exhaust fumes for dinner during la Corniche runs, and simply taking like a champ the daily barrage to the senses that is life in the city, hearing from my host aunt that la poussière had arrived initially caused little alarm. At 8:20 sharp, I bid her a bonne journée, tucked half a baguette in my backpack, walked myself out the front door, and five minutes later walked my sorry ass back in.

Whoops.

Even with a sheepishly-taken handkerchief over my face, being outside just, well, sucks… Nothing, and no one, is impermeable to the choking blanket. But interestingly, everything else seems perfectly average, as if some higher power’s thrown down a special effect on a looping film: Now Playing! Groundhog Day: Dakar Characteristics.

Left and right, people are simply going about their business. The fruit vendors beat off their products nonchalantly with little whisk brooms. Traffic might be slightly slower, and the car horns more agitated, but the plodding street cows don’t seem to mind. Taxi drivers and customers barter as rapidly as ever over prices, gesturing animatedly around the obstacle of DIY face coverings.

In essence, the delicate city dance is moving exactly as expected. It’s just a masked dance, I guess.

So, taking only this into account, le jour de poussière has already been one of those “Something to Write Home About” kinds of days. Oh, and to top it off, it’s Mardi Gras.

Go figure.

As the coastline continues to rush by, and my eyes lilt blearily open and closed, I feel a strong hit of déjà vu — conjuring up a certain morning, on a certain train, crossing a certain inky river. My mind is plunged back to icy waters. But perhaps that’s just wishful thinking.

For what I’m seeing, and what I’ve only just seen, are so, so different than the Mississippi, or my campus; my home region, or home life.

Despite the unfortunate conditions, our Environment & Sustainability class is just returning from a field excursion to an outskirt of Dakar that’s hard to define. Slum isn’t quite the right word; ghetto isn’t either. Those imply forced, or at least de facto, habitation by a certain, usually minority group of people. That’s not the case here, though. Two long hours ago, when we first turn onto the alley street marking our entrance to the area, our professor describes it differently, and succinctly: non-planifié.

This, finally, is the right word, as what we’re seeing embodies the nature of unplanned. No one, physically, is supposed to live here — the local government doesn’t encourage it whatsoever. Some years back, the land was built on, then abandoned, as it turned out so naturally unstable that many buildings began submerging into the soil. But a place to live is a place to live, especially in a congested metropolis, so people have returned nevertheless, attempting to make the best of the piecemeal infrastructure.

At this particular street, a long, uneven tongue of dirt pack offers a snaking channel into the neighborhood. Following the quick briefing from our professor, we begin to make our way through slowly. I’m already sweating bullets, and each huff into my mask is infused with a slight mineral tang. None of us say much.

As we balance beam our way around a smelly, stagnant pool spanning most of the alley’s width, three little girls in matching, immaculate Mardi Gras dresses pass in the opposite direction. They trail their mother like colorful ducklings as she too navigates the rust-colored water.

This neighborhood has grossly inadequate sanitation, with its streets often turning to sewage channels, yet most ramshackle houses open directly onto them. You can read the history of many by their appearance, since the majority have undergone continuous sinking and rebuilding. It’s a bit like pulling ice core samples: the newest constructions are on top, with clear delineations between time periods as you go down — each marking a sad losing battle with nature. The residents, though, are friendly, with several asking curiously what a group like ours is doing, no less on a day like today. Many maintain little street-side boutiques and storefronts, which look no less inviting than those in other areas of Dakar.

The dichotomy, then, between these people and this place is shocking: well-kept vs. sordid, proud vs. neglected. Yet this, we’ve learned, is often the case in Senegal: cleanliness and personal presentation are culturally critical, no matter if one’s surrounding environments are polluted or left to the wayside.

As we continue, a huge patch of green, easily the largest I’ve seen in Dakar, pops up around a corner. I get excited, and then not, for it’s no lush park. This is a retention marsh to help stem rainy season floods — filled with reedy plants resembling mid-season corn — but it’s filthy. Like so many shared outdoor spaces around the city, our teacher tells us, residents have made it their collective dumping ground.

As if to prove this point, a woman tips an enormous wash bin of wastewater directly over the fence as we pass. When I look closer I see a young man, perhaps my age, bucket bathing completely naked amongst the floating trash and sewage, no more than 15 feet from the spot. A hard lump knots in my throat.

We move along nevertheless, but la poussière is taking its toll. Soon, we complete our loop, and pass a different neighborhood border crossing. Here, the vibe takes a 180-degree turn. This is a busy market street with bright colors and aggressive vendors. The dust seems only to amplify the chaos, with cars and scooters and shoppers rushing quickly from A to B. In short, it’s the last place I want to be right now. I feel a bit shellshocked, and overwhelmed with everything we’ve experienced.

Many people are masked today, but those we’ve seen in this quartier non-planifié seem perhaps the most.

While at first glance everyone’s more homogenous with covered faces — anonymously facing the same suffering — this is its own sort of mirage. Because even in dust storms, there’s a divide between the have’s and have-not’s. On days like this, we learn, stores the city over run out quickly of their expensive, industrial masks. Our program staff, in fact, were barely able to acquire them for us.

Folks here, on the other hand, have to largely make do themselves. In front of one small shop, for instance, I glimpse a man handing out bright blue Delta Airlines eye masks for makeshift breathing protection. He throws their wrappers on the ground. Like usual, this isn’t the only out-of-place, Western relic that pops up: another man has an “insight.com bowl” college football polo pulled up over his nose and mouth. And as we pile into a taxi for home, our driver chucking his plastic coffee cup aside, Obama’s ’08 campaign logo becomes visible on a nearby brick wall.

But maybe this is beyond the point. Because in this poverty-stricken area, during the immediacy of la poussière, many choose not to cover up at all. I’m not really sure why. Perhaps they’re more used to living out the conditions; or perhaps they’ve just faced worse than some dust.

I learned the name of this place today, and then immediately forgot it. Through this experience, its veil was lifted oh so momentarily — but already, it’s going back to being as masked as it ever was.

Fils + Racines

Note: This was written throughout my fifth and sixth weeks in Senegal, and posted on 2/27. More pictures hopefully coming soon!

It’s sitting under the broken shade of a huge baobab tree in a far-flung village that I begin to piece something together. More squatting, really, on a cookie crumble cinder block, I, along with my group, am squinting and coughing my way through a discussion with an Arabic schoolteacher punctuated by frequent sandy gusts. The surprisingly young man is telling us (through translation) all about his school’s place in the Senegalese educational system — one that is itself surprising, in its complexity and degree of variance.

The school in question is off to our side about 50 feet, all three rooms, slat roof, and cinder walls of it. Though it’s an early Saturday afternoon, several dozen high-pitched voices chorus strongly, floating over strains of song one can only assume convey joy over this lengthy recess from their teacher. The local children who attend French primary school frolic around even more freely — the brave clamoring to be near us, the shy peeking from a distance, the stoic ringing the circle like bodyguards — as they don’t have class on weekends.

A fact which, speaking of lessons, offered a crash course in Mob Maneuvering 101 less than an hour ago. Pulling off the hard pack road unsuspectingly, we would soon descend into the Senegalese village version of a paparazzi firestorm. Through a gauntlet of shaking small hands, shouting dozens of Bonjour’s! Salaam Maalekum’s! Ça va’s?! — all the while wading thickly through the fray — we would then parade march with at least 50 kids and our program staff to various local people + places of importance.

That’s what this whole weekend has been, in essence: a whirlwind. 16 people who still lack any simple title — toubabs, foreigners, Dakarians, college juniors, Wolof-mumblers — scuttling around on a bus like some manic, extraordinarily out-of-place beetle.

We’re in the south-western region of Fatick, but more specifically near Toubacouta, which depending on your perspective is either: A. a large village, B. a small town, or C. a welcome oasis away from Dakar smog (I’m locking in this last one).

Though this is our first multi-day excursion out of the city as a group, it’s far from a beach vacation. In the past 48 hours, we’ve had site visits at a local health post (staff: 1 médécin + 1 mid-wife), a mangrove forest (wild hog encounters: 1), a French primary school, with a group of women regarding microfinance, at a women’s community garden, and now… whew… this. It’s a tiring routine for an unacquainted city beetle: absorb the sights and info, ask questions, scuttle; other sights, more info, questions, scuttle; pause, eat, drink tea, scuttle…

Which is perhaps why, in addition to a certain butt getting sorer and certain face sandier, my attention drifts away from the topic at hand (“factors parents weigh between Arabic and French schools”). There’s a second baobab straight out from me a ways, a grand, old one which seems to look on pityingly — at these poor creatures withering in the bone-dryness. Between the two is a rickety utility pole, jabbed down like an errant toothpick, propping a power line that from my angle stretches directly from tree into tree.

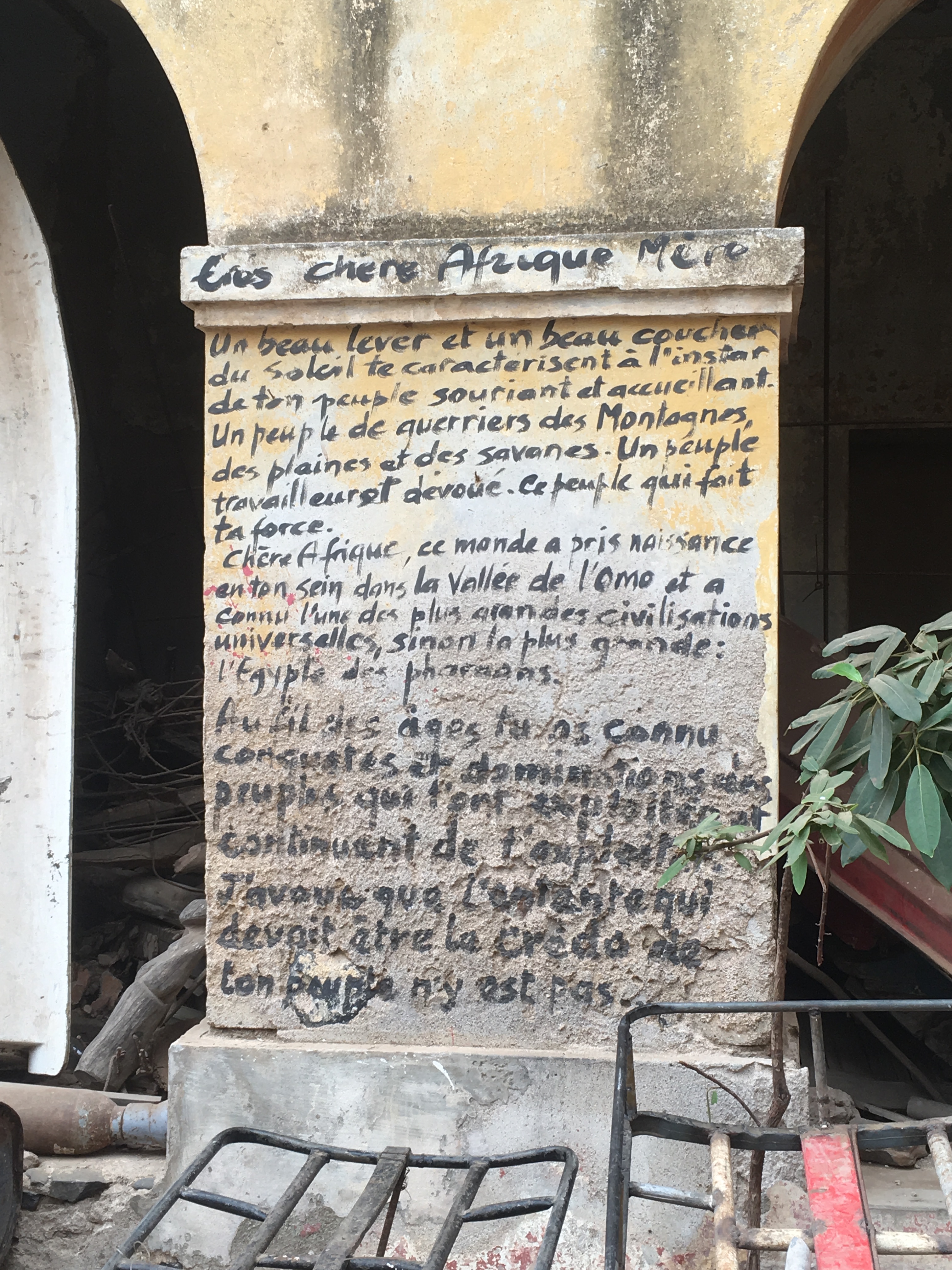

It’s a funny juxtaposition: two baobabs, treasured symbols of Senegal, strung carelessly by a random wire, international symbol of genericness. The former a racine, a root; the latter a fil, a thread, a connector.

Sometime, on some wall, somewhere during our trek from Dakar, I remember passing a block-letter slogan fading away like bygone propaganda: “L’éducation est le meilleur passeport pour l’avenir”

Education, as we’ve been seeing first hand, while varying in its forms and quality, is certainly deeply enracinée in Senegalese culture. Religious education, family education, formal education; though many embody past traditionalism, it makes a good deal of sense that their continued existence is probably the “best passport for the future.”

On a later Lego heap of bricks read a much easier message to decode: “Re-election Macky 2019”

People had high hopes, really high hopes, for Mr. Sall, fourth-ever President of the Republic. He was supposed to be a catalyst, a fil, an Obama-like fresh face bridging the progressive reformism of the young generation with the boomer-like staunchness of the older one — an attitude embodied by his ancient, corrupted predecessor, Abdoulaye Wade.

But, by and large, many people view his tenure as a disappointment. He hasn’t brought any sweeping social changes, hasn’t fought the incredible lobbying influence of Senegal’s Islamic Brotherhoods (amongst other religious powerhouses). He hasn’t done much to advocate for the nation’s extraction from exploitative post-colonial dependencies on France and others, but has managed to paste his face on every random place possible — storefronts, billboards, murals, buses. Recently, I literally saw his cut-out on the butt of a woman’s skirt. It’s as if he’s toeing the political line gingerly, one foot on the fil but never quite out of reach of the ol’ tree.

Or how about this very village, a perfect embodiment of the tension between past and modern, root and shoot? One in which the children are floored by our presence, yet sport Barcelona jerseys and spray paint Messi on the walls, homages to heroes a world away; in which small satellite dishes adorned with Chinese flag logos post over single-room homes like foreign sentries; and where a woman ceremoniously presents a seat at our discussion to the highest elder of the village, steps away, then whips out her smartphone to document the moment.

Or what does it mean that similar scenes refract once more just hours later, at a traditional Senegalese wrestling match we attend in a different town?

It’s a chaotic scene — primal and laced with energy — les lutteurs stomping around in a sandy pit, all muscle and loincloth and grimace, their limbs bulging with holy talismans and bodies sopping with specially-blessed liquids. Music and dance are integral to the tradition, so drummers pound out steady rhythms while two older women trade lines into microphones. Occasionally, hype men will bust out their best moves, whipping the crowd into cheers.

The cord establishing the ring, though, might as well split two entire time periods, like the magical divide in Field of Dreams. Outside, almost every young, male spectator screams NBA or soccer fandom. Messi’s and Lebron’s, Lakers and Heat and Barça’s, of course, comprise the majority, but I’m mostly shocked to glimpse my Green Bay Packers peeking out on a little boy’s sweatshirt. As for the young women, blue light screens illuminate them giggling in packs, most wearing jeans, faux luxury brand t-shirts, and flaunting tressed up hair and jewelry. There are elders too, given the importance of this community event, who sit more respectfully but not any less engaged, in colorful dresses and handsome boubous.

Normally, these tournaments take many hours, or even multiple days, to crown a champion. For us, they’ve condensed to a single evening, which passes thrillingly, with only a single intermission during which our group is “encouraged” (read: forced) to show off our amateur Senegalese dance abilities — to the crowd’s obvious delight. We sit back down, all shamefully gassed given the level of fitness on display. In not too long, one huge man forces another huge man to thud on the sand, and tonight’s victor is crowned. The prize? Not a giant check, but a 50-kilo bag of rice, that our champion hoists as if he’s only just warmed up.

Still, it’s an exhausting event, even for the viewer. In Senegal, the popularity of this ancient sport isn’t currently wavering, but the world around it certainly is. The young fanbase remains energized for the moment, but as the Chinese keep installing tech, internet + media consumption rise and global influences continue pressing in, you have to wonder if one day these fans might just avoid the hassle, and take Lebron over la lutte.

So, it’s sitting under the broken shade of a huge baobab in a far-flung village that I begin to see just how unique this moment in time is — for the people, for the communities, for the nation. But roots and wires don’t offer up many answers, just a lot of questions (not least how to avoid choking down bits of sand…). Through four short days, I’m left pondering:

Which education really is the best passport? Traditional or modern? Religious or secular? A hybrid?

Is Macky truly at fault here, or is he perhaps a symptom of an infantile democracy, imposed suddenly only 60 years ago by a retreating foreign power? Can the system possibly bridge all of the variance within the country?

What will be the result of this clashing dissonance of tradition and modernization? Especially between generations forever rooted together, but tied to the wider world in such different ways?

And, maybe most of all: When should certain roots be uprooted, and when should some linkages not be strung?

Pretty soon, we’ll pack up for the last time and scuttle our way back to Dakar. Though it’s been a great trip, I’m looking forward to seeing my family, getting back into the city rhythm, and perhaps running over to a certain friendly gym. But I’ll remember the baobab, think of the power line, and next time, for my smog and sand-weakened lungs, maybe bring a mask.

People’s Republics + People’s Gyms

Note: This was written throughout my third week in Dakar, and posted on 2/10.

Stumbling upon Sino-Senegalese relations in Dakar really wasn’t purposeful.

Let me preface: To the huge surprise of no one more than myself, I’ve been running a fair amount over my first three weeks here. Many evenings have caught me pounding dangerously uneven pavement, dodging vendors waving faux leather wallets in my face, and frequenting one gym in particular.

This gym, though, isn’t really a gym at all, and also sports a curious name: Espace Sportif de l’Amitié Sino-Sénégalaise

Roughly translated as: Athletic Area of Sino-Senegalese Friendship

Huh.

Now, I like to think that I’m a little bit more familiar with China than the average American bear. I spent three incredible weeks in and around Beijing during high school on a summer abroad program. I’m still closely connected to a number of friends + contacts over there. I’ve since read books and follow news on China closely. It’s a global superpower, and has its hand in places the world over — including, I know somewhat controversially, Africa. But of all the pockets of Chinese influence I may have foreseen in Senegal, this one would never have struck.

The friendly workout space is a small strip of land, pasted like a peel-off mustache in between two formidable forces: la Corniche, a backed-up Dakarian vein of a road, and the Atlantic Ocean. Each evening, however, the unassuming demilitarized-like zone perhaps 60ft at its widest transforms into its own cacophony. Hundreds of locals pour in with religious-like fervor: young men in tautly-stretched football jerseys pumping out pull-ups and bench presses on rusty racks, middle-aged women clustered tightly in yoga mat circles for ab sessions, elderly men walking slow laps around the organized chaos.

The entrance sign I trot by proudly proclaims that the area is a “gift from the Embassy of the People’s Republic and Chinese Enterprises to the Mayor of Dakar, 2016.”

It’s no lie — the Chinese-Senegalese friendship, whatever side effects that may entail, has certainly funded quite something here: exercise equipment spanning at least a hundred yards, all slightly spartan in their utilitarianism and hard use.

As a whole, I can tell that Dakar is many things — noisy, dust-choked, rapidly expanding — but unfit is not one of them.

Long-established isn’t one of them, either. In its current form, Senegal is a very young country. Sitting President Macky Sall is only the fourth in the nation’s history. France formally withdrew in 1960, yet still wields major sway over the economics, politics, and development of their former colony — the widely disdained CFA currency being but one infamous legacy. Senegal is relatively resource-poor, exports very little, and rarely makes headlines: I mean, when was the last time you heard them covered by international news?

Which is what makes it all the more bizarre the first time I pulled to a stop, huffing lungfuls of exhaust-tinged air, and glimpsed this random product of globalization and international affairs. You can’t ignore the irony: What is China, by numerous metrics the world’s top polluter, doing financing a random outdoor fitness area in a polluted zone of a polluted African city?

Because yes, the pollution, second only to the humming energy of the people here, is unmissable. I know full well that running in a city with known particulate levels exceeding five-fold the recommendations of the World Health Organization probably does me as much harm as good. The craggy ocean breeze does its best, but the stench of backed up traffic can’t be fully masked. It also can’t sweep away another sobering aspect of the amicable arm farm: the trash.

The country has a major problem with waste. Microplastics, intact plastics, rotting food, household wastes, unidentifiable wastes, you name it… they all choke the arteries of Dakar like a cholesterol the exercising masses are trying to avoid.

Fairly recently, China imposed restrictions on imports of most U.S. recyclables. Well, that’s not a problem here, because in Senegal there is no recycling — at least not in the widespread municipal sense we know. My host family tosses everything, from light bulbs to Coke bottles, and the government has done practically nothing in the way of policy development over the past few decades.

Plastic pollution is especially bad, which poses grave environmental and social costs for a nation relying heavily on fishing + coastal-related tourism. It’s a tragic dichotomy to experience at the gym: I’m able to do pull-ups facing the setting sun over the Atlantic, while in the foreground, a rainbow of trash tarnishes the panorama.

An environmental ethic, or at least basic concept of sustainability, simply isn’t present here — which pains me viscerally. But then again, as with so many aftershocks of post-colonial existence — from the most macro to most micro levels — perhaps the people just haven’t been afforded the opportunity to develop it yet.

In a country where the annual per capita GDP is about $1500, and issues of caste, gender, inequality, and corruption scar deeply, the lifecycle of a plastic bottle just isn’t the most pressing concern. The term minimum vital came up in our first environmental class here: living necessities. If these aren’t adequately met, long before considering other societal issues, the ability of individuals to engage with environmental issues is near impossible.

In other words, sustainability is reserved to the privileged.

Is it out of cruelty, then, that Senegalese sip water from little plastic bags the perfect size for a sea turtle’s head? Or out of spite that thousands upon thousands of single-serve Nescafe cups are literally tossed on the ground every day by local residents?

I don’t know.

A better question, maybe: given that the entire African continent contributes only 2-4% of annual global carbon emissions, yet bear their effects unduly, would a certain amount of apathy be understandable?

This problem, then, is both Senegal’s fault, and it’s not. It’s both China’s fault, and the U.S’s fault — and every living consumer’s fault — and it’s not. Sustainability is the ultimate long game, with no easy culprits to prosecute, especially between very different global actors.

Because it does sometimes feel like a different world here. This city doesn’t have the fortune of green space, at least not according to the definition of wealthier nations. The Dakar peninsula juts out like a microplastic fragment of the continent itself, all sand-blasted pavement and squat buildings, tempered colors and crazy cats and oh so many people. There is no Central Park to bask in, no Mississippi riverfront, no well-kept natural refuges. Already, I miss the sanctity of sweet air, and cool grass, and days lived under forested canopies.

But still, it all seems to work out alright. The kids across the street from my house kick around happily in rough sand pockmarked by litter — le foot in this footing is a better workout, anyways. Rusty hoops awning dirt courts look like tetanus-in-a-dunk, and surely lopsided, but teenaged Lebron James’ sport their 23’s nevertheless, living out hoop dreams under a sweltering sun. The ladies in their mat circles don’t seem to mind their lack of idyllic nature vistas, or the swirling street chaos surrounding them.

Which wheels back around to the Sino-Senegalese Athletic Area that, lest you forgot, is also steeped in Friendship. All sarcasm aside, this isn’t far from the truth. It’s a genuinely enjoyable place. The people-watching is second-to-none. I’m able to shake out my legs at the edge of scenic cliffs. Everyone is focused but affable. There, you feel a part of something bigger, even if dwarfed by your surroundings — or perhaps especially so.

I guess this is just another one of those inattendu’s. Day after day, you lace up your dusty sneakers, pound the cracked sidewalks, and find yourself some curious links between past and present, oppression and sustainability, Senegal and China, these hard-sweating people and the outside world.

So, I’ll keep coming back (as long as my lungs will allow). The finding wasn’t purposeful, but the returns certainly will be.

Tendances + Inattendus

Note: This was written throughout my second week in Dakar, and posted on 2/2.

Today’s alarm clock isn’t one of the usual suspects. After just over one week of becoming accustomed to the requisite pattern — rooster, crazy cat, goat, crazy cat, human, crazy cat — this new morning sound piques my interest.

As sandal-clad and bleary-eyed as ever, I jimmy the old iron key and peer out at one of the last sights one would expect on a Wednesday before breakfast: their host cousin, huffing down the common room stairs in his nightshirt and underwear, yanking on the leash of one very pissed-off sheep. Mentally filing this away to the “Something to Write Home About” category of memory, I register simultaneously another interesting revelation — that I’m not altogether surprised.

There is “une tendance à ne rien faire” here in Senegal — a tendency to move slowly, to go about life deliberately. Although nothing, admittedly, is smooth about Papa’s sheep-herding, the reason for the animal’s being here is the ultimate in thoughtful + communal.

See, my family, like the vast majority of the population, is Muslim, and exactly eight days ago, Papa’s wife Kumba gave birth to a baby girl. She’s beautiful, and healthy, but as of yet unnamed. All of this is to understate that today, then, is a very important day — the baptism, an all-day celebration and naming ceremony with well over a hundred expected to be in and out of our small house over the next 12 hours.

So perhaps you’ve put two-and-two together: sheep + religious protocol + many mouths to feed = bad news for sheep.

Despite the animal’s resistance, her eyes are soft, pretty, and something clenches in my gut. A ridiculous thought floats to mind: Couldn’t we, like, sacrifice a bushel of soybeans and cook those instead??

The feeling certainly isn’t lessened when, upon rushing back from morning class, I’m promptly made to hold a dripping sheep leg (file that image away, too). But I know that this tradition, like so many aspects of life here, is simply an inattendu — an unexpected. These things manifest randomly, in every place you don’t think to look; say, out your bedroom door.

They’re also, quite literally, around every corner. In Dakar, one quickly learns that you don’t hail a taxi… the taxi hails you. Armed with cute-sounding horns, a penchant for rapid bartering, and never the right amount of change their patrons need (Senegalese society is almost entirely cash-based), Dakar’s drivers prowl the streets day and night searching for unknowing prey.

To take one is both a step back in time and a helluva wild ride; as most cabs themselves are beat-up, black-and-yellow Renault’s and VW’s decades out of production. The hoods sometimes smoke, seatbelts are discouraged, yet drivers wind expertly — almost casually — between the street-cows, narrow market alleys, and legions of other motorized bumblebees clogging their way.

When walking the streets, everyone’s always trying to sell you something — from bagged peanuts to knockoff football jerseys to literally themselves for marriage — and taxis are no exception. They beep, the vendors spout, hopefully and sometimes aggressively, then you usually signal them away. It’s the delicate city dance, except instead of sugar plum ferries it’s wide-eyed students and men hollering in Wolof.

If the traveling is hectic, however, the arrival almost never is. “Senegalese time,” as it’s affectionately teased, cannot be described as punctual. Starting a little bit (or a lotta bit) later than expected isn’t rude, it’s relaxed; lunches equate to siestas, and siestas can run all the way to the next meal. The stress is low, and contentedness high. It’s a marked change for many of us, so used to overflowing Google Calendars, meals-on-the-run, and our implied academic + cultural necessity of constant productivity. Here, though, a strict schedule is more an interruption of resting time, rather than vice versa.

So far, there’s been something difficult, and a little uncomfortable, about this. My family isn’t there to coddle me, or be my personal tour guides + entertainers — after all, they’re busy prepping sheep and cooking up feasts. Our teachers and program staff aren’t either. They’re wonderful, but life outside the classroom is ours to fill, which can be daunting. Compound this with the fact that many of our families have little or no wifi, no TVs, video games or Netflix, and you create a concoction for a lot of time: free time, thinking time, presence time.

In this way, it’s an inattendu, but it’s also really refreshing.

After all, the unexpected’s are why I’m here. Why any of us toubabs are here. The point of studying abroad isn’t to mold the host culture to your values and lifestyles, it’s to be a sponge for theirs. Some days you soak it all up — the French, the Wolof, the sensory overload that is your city and your family — while others you feel wrung out to dry. No matter how much soap you apply, somehow you’re still papered with residues (ah, Dakar’s famed dustiness…). Finally, after all the day’s dishes are done, you’re left somehow different than you were before — and ready to do it all again tomorrow.

There is “une tendance à ne rien faire” here, but that doesn’t mean that nothing ever gets done. After all, I have a baptism party to get back to. And if all that actually means is sitting around, sharing words, food, and time together — sponging it up as best I can — then, really, I couldn’t hope for anything more.

Week #2 Photos

News + Nots

Note: This was written throughout my first week in Dakar, and posted on 1/25.

It’s 6:30AM again, and I’m starting to wonder why I even bother to set alarms. Just like one short week ago on the train, my brain meanders its way through through several sleep-addled thoughts:

- Early mornings and I don’t get along…

- Why does my bed fold itself around me like a taco shell?

- When will this crazy cat shut up?!

Let me explain. I love cats, which is the weird thing, but on and off for what feels like three hours I can only believe that someone’s beating the poor thing with a bag of rocks: a bone-chilling yowl, followed by a period of rest for the beater, repeat.

It’s not in fact, though, nearly the only element of cacophony that’s pulled me from dreamland. In quick succession, I’ve also heard the two goats next door bleat, a rooster start caw-cawing with cat-like vigor, and the day’s first call to prayer echo throughout the neighborhood.

This neighborhood is Mermoz, and this house — in all of its craziness — is my family’s. My host family’s. Sandwiched between two other rickety, rowhouse-type buildings, chez moi resides squarely in the midst of one of Dakar’s bustling residential areas.

The rooster seems more urgent, so I sit up and rub the grit out of my eyes. Outside my window to our open-air, courtyard-style dining room, I hear the first strains of hushed Wolof passing back-and-forth between family members. Soon, my Maman will be downstairs with tea and baguettes, and I’ll greet her warmly — with only a few stumbled words. The trickly shower I take will be cold, but the food warm.

For the moment, though, as I soak it all in, I’m hit with a wave of something extremely peaceful.

If I wanted to, I could view the past week as a series of nots. I was not expecting family living to be so radically different, not prepared for the onslaught of people I’d be asked to know; I’m unable to communicate with my family in their primary language, and not prepared to navigate Dakar myself. I am — quite simply — not Sénégalais, and never will be.

Yet, a hop, skip, and 5000 miles later, I’m here. Life is different, life is simpler, but life is good. Around a knee-high wooden table that Maman rolls out from the corner, we eat from the same platter with our bare, right hands. I talk NBA basketball with my adult brother, and Playstation FIFA with my teenage one. My two-year-old sister snuggles up close when we watch Rio en français. And, the 16 of us newly-minted Senegalese toubabs (see: foreigners) — despite it all — are finding our way.

Through our first walking commutes to the West African Research Center, and hair-raising cab rides weaving through colorful markets + polluted dust clouds + cows roaming the street. Through learning the aching way which water can be trusted, and which people cannot. And, outside the urban oasis that is our shaded, French colonial-style school, by being left to our devices to figure the rest out. The good, the bad, the awkward, the confusing, exhausting, nerve-wracking, and new.

New… that’s a good way to put it. New, not not. A series of news pulling us in every which way this first week in this first period of this new experience.

For now, though, the rooster’s crow cuts through, reminding of the hour. I rock off the bed and slide on a pair of sandals. A rendez-vous with icy water awaits, then breakfast and greetings. Finally, I’ll shoulder my backpack, open the front door, and step out into the bustle of this city — and life — that I know in due time, surely won’t feel so new after all.

Week #1 Photos

Departures + Destinations

Note: This is being posted concurrently with the above entry, News + Nots, but was written on 1/18, the day of my departure.

The Mississippi looks cold today. Mottled in the glass by the haze of my own reflection, chunks of milky ice drift starkly against the black current, framed by an inky dawn’s sky. I lean my head against the train door, and watch blearily as the river ebbs, flows, and is quickly whisked out of sight. The short hand has just since hit-and-run on 7, while through my own hands runs a shiver.

Any sane mother would kill me this morning. I’m woefully underdressed for what is the aftermath of a major winter storm — my jacket’s in the closet, boots in their cubby shelf, snowpan… well, I wouldn’t wear those anyways. Basically, on this day that could be any other in Minnesota, the Midwest didn’t decide to see me off kindly with hugs or flowers.

Who am I kidding, though? I suppose I wouldn’t really want it any other way.

I’ll miss the ol’ frozen tundra, at least a bit. Just like I’ll miss this river, and this campus I’m departing — a once home-away-from-home that has truly, in fact, become my home.

The wheels keep up their clack-clacking, and the train rolls on. A homeless-looking man slumped on a chair, and who sports a Fu Manchu-like moustache, suddenly looks up and asks if I’m from New York. The question catches me fully by surprise, not just because I’m shaken from my meandering thoughts, but because I am indeed flying to the Big Apple in three hours time.

“Hm, oh n-no I’m not,” I stammer out eloquently. I tell him I go to the nearby university, but I’m headed to the airport, with a slight laugh over both the question and my reaction.

“Huh, well you look like it, look like you maybe got money,” he replies, not unkindly.

I let him know that I don’t, really, and we both chuckle when he jokes that, if not for his “wife leaving, and dog biting” him, he’d have gone to school as well.

But as I reach and readjust the blue strap of my admittedly pricey backpacking bag, I feel a twinge of something else. I too, can joke — about my unpreparedness, about how I’d love to nod off against the cool glass, or how strongly this man calls to mind the notorious supervillain in mid-life crisis. But in truth, I must acknowledge that my entire life has profited from the incredible fortune of preparation: from my high, high-quality education, to the stability of my family, to what having access to relative wealth and adequate resources means in this most wealthy period of humanity’s existence.

Despite anyone’s best intentions, privilege will always have many conundrums. And this is a case-in-point example. It’s clear to this man, at least, by my appearance, sewn into my clothes and possessions, and evident perhaps most of all in my destination.

I stand, he sits for a few moments in silence; then the doors slide open. Our eyes meet and I wish him a good day. I’ve got a plane to catch, and another train to take me there. When the tundra air hits I again shiver, and my mind is plunged back into icy waters.

The Mississippi looked cold today, but I’m headed somewhere new — somewhere warm. I pause on the platform, getting my bearings, and glance back at the departing car. I hope he stays warm, too.